Does Tylenol cause autism? It’s a question that has been heavily debated for one reason: a celebrity made that claim. Famous names get attention, but being famous is not the same as being knowledgeable or even trustworthy. After much research, I have compiled several statements made by celebrities that range from slightly offensive to extremely harmful. Some, even when checked against scientific studies or verifiable records, fall apart or at least become far less credible than they initially appear. Some are just plain objectively false.

In the mid-2000s, actress Jenny McCarthy introduced the idea and then became the face of the false notion that childhood vaccines cause autism. She built an entire platform on this claim, despite overwhelming scientific evidence that proved her point incorrect. The CDC and countless other peer-reviewed studies have since confirmed: vaccines do not cause autism. Autism is strongly influenced by genetics and other complex factors, not immunizations.

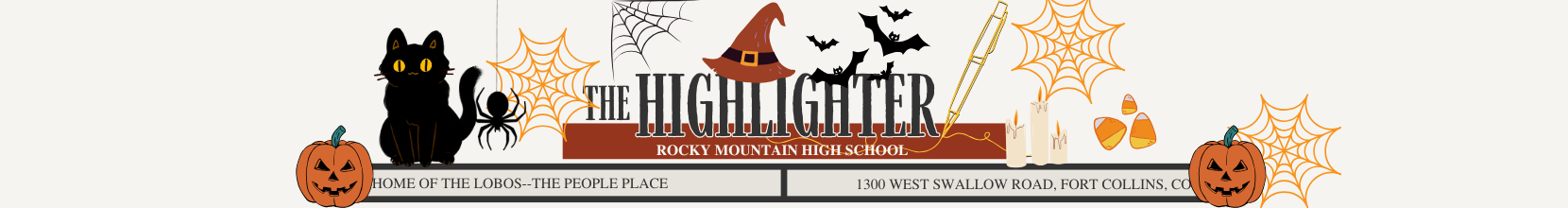

Once the vaccine-autism myth was widely debunked, the narrative didn’t disappear. The supposed correlation simply shifted scapegoats. McCarthy’s rhetoric left many parents fearful, although the evidence was strongly against her. So, parents started looking for another culprit to explain autism. That’s when other public figures, including President Donald Trump, picked up the claim that Tylenol (name-brand acetaminophen), used during pregnancy, might cause autism.

Although some observational studies have found weak associations between prenatal acetaminophen use and developmental outcomes like ADHD or autism, many scientists point out that association is not causation. Mothers who take Tylenol often do so because of a fever or infection. The conditions themselves have evidence of influencing fetal development, not the over-the-counter medication. Large-scale research, including studies in Sweden with over a million children, shows that once confounding factors are considered, the supposed link between Tylenol and autism largely disappears.

Health authorities, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the World Health Organization, and the CDC, all agree there is no proof that Tylenol causes autism. And, it remains one of the safest options for managing pain and fever in pregnancy when used as instructed.

On the more lighthearted end of celebrities as experts: SZA, an American singer and songwriter, confessed that some prior public characterizations of her academic background were possibly misleading. Later, she admitted in interviews that she attended Delaware State for two semesters and then dropped out.

In earlier interviews, SZA was reported to have claimed she had a degree in marine biology from an Ivy League school. In a 2023 Elle interview, she admitted the reality: she attended Delaware State for two semesters, stopped going to class, and ultimately flunked out.

The contrast between the glamorous version (“Ivy League marine biologist turned pop star”) and the actual version (“college dropout with a great voice”) has been highlighted in outlets like Vice. Whether it was a misunderstanding, a PR embellishment, or SZA herself leaning into a shinier backstory, the fact remains that her Ivy League credentials are a myth.

Leaning back into the more controversial end of misinformation. Some celebrities, social influencers, or public figures pushed the idea that 5G cellular towers either caused or exacerbated COVID-19.

Coda Story’s investigative reporting catalogs numerous celebrities who spread 5G–Covid disinformation, illustrating how this conspiracy gained traction despite scientific debunking. The reach of these messages was large: one study cited from Oxford’s Reuters Institute estimated that politicians, celebrities, and other high-influence figures produced about 20% of all coronavirus misinformation, and that their content accounted for 69% of all social media engagement with misleading COVID-19 content. Everything they were spreading was in fact, false, with much research debunking it.

UNICEF (Montenegro) published a clear statement: 5G technology does not cause or spread coronavirus and seems driven more by fear, misunderstanding, and distrust than by actual technical or medical issues.

A peer-reviewed article by the National Library of Medicine explicitly reviews the claim and rejects any link between 5G radio waves and COVID-19. The authors note that “viruses don’t propagate via electromagnetic waves, and there is no plausible biological mechanism for such a link.”

A U.S. congressional hearing (documented in House records) addressed disinformation, including allegations surrounding 5G towers and their connection to COVID-19. It highlights the fact that the claim was treated seriously enough by legislators to be officially examined.

When summarizing all of the examples given, there is a simple moral: celebrities provide misinformation for many reasons.

Jenny McCarthy’s original “vaccine causes autism” claim was thoroughly disproven, but it left a plethora of new, equally scary scapegoats, including Tylenol, being the latest example. In both cases, misinformation overstated weak evidence and spread unnecessary fear. SZA is an example of reputation-building through a selective presentation of facts. Claiming or simply implying an Ivy League degree in marine biology, when that is objectively not accurate, misleads fans about credentials and even trustworthiness. The public record officially undermines the earlier narrative. The idea that 5G towers caused or even helped in the development of COVID-19 is perhaps one of the clearest examples: the celebrity’s claims go against basic science about viruses, radiation, and disease. The claim violates basic scientific principles, and all major health institutions reject the link. This is a strong case for how celebrities can amplify pseudoscience to large audiences.

Many celebrity claims don’t hold up under scientific scrutiny or public record. Misinformation helps spread confusion, fear, or false authority. Evaluating claims requires checking original data, peer-reviewed studies, and expert consensus rather than relying on pure fame.

In science, it’s often impossible to prove something objectively to the public, even if it’s completely false. What researchers can do is show when claims go beyond the available evidence. This is especially true in health and medicine, where many complex factors are at play. A weak statistical link is not the same as proving causation. Still, celebrities sometimes make or repeat bold claims before the facts are fully understood, whether because of marketing, controlling their public image, or giving an audience what it wants. So, if you heard nothing else, hear this: please do your own research before you believe a random, possibly harmful fact from a celebrity you trust.